Town halls – a manifestation of political order

Text: Fredrik Torisson

Most of us have some idea of how a town hall works, what is housed within it, and why it exists at all. Usually, this idea is rather vague. We can imagine a typical town hall – perhaps in our own hometown – to act as a stand-in for town halls in general. If we let go of that one town hall for a moment and instead compare a few other town halls, we'll soon discover that there are major differences; the more town halls we compare, the more significant these become. This is true not only of the buildings themselves, but also of how we describe them. What is the difference between a rådhus (literally 'council house') and a kommunalhus or a kommunhus (literally ‘municipal house’)? Copenhagen has a rådhus, whilst Stockholm has both a stadshus and a rådhus. European terminology varies, too: German cities have a Rathaus and French a Hôtel de ville, Italian cities have a Palazzo pubblico, whilst American cities have City Halls, Dutch have a Stadhuis, and British cities may have Guildhall or a Town Hall, which in Scotland may be a Town House – and so on. As plentiful as the names for the building may be, they all share the same function: they are the building from which the city is governed. As such, they may be said to belong to the same family of buildings, and in spite of their differences, they share certain characteristics. This text uses ’town hall’ as an umbrella term for this family or building type.

The history of the town hall goes back at least 800 years. Naturally, the design and functions of town halls have changed over time, depending on where they are. Despite these variations, many features recur repeatedly, in new constellations, under new conditions and with new significance. Copenhagen City Hall was inspired by the medieval town hall in Siena; many of the visual features for Stockholm City Hall were borrowed from Piazza San Marco and Palazzo Ducale in Venice. We can say that town halls allude to other, earlier town halls in different ways, both in their exterior appearance and – perhaps to an even greater extent – through their building elements. On the whole, then, we might rather paradoxically say that the history of the town hall is characterised by divergence as well as repetition. We can also conclude that the history of the town hall is by no means linear; instead, it is like a web whose threads weave in and out, back and forth.

What, then, can be said to characterise the town hall as a building typology? What is the lowest common denominator? There is no straightforward answer to this question, but for the sake of simplification we might look at three roles of the town hall in a city or town. Town halls play all of these roles simultaneously, but how they are interpreted and prioritised is a matter that varies from one case to the next.

Firstly: the town hall – including the space in front of it – is the stage for the city's political life. The town hall is the space in which those who are permitted to speak can influence the city's politics, and those who stand outside, both literally and figuratively, can try to make their voices heard. Beyond formal politics, the town hall is also in an extended sense a social, or an informal stage for the city's elite, who often compete to demonstrate their status through their proximity to the centre of political power.

Second: the town hall is the seat of the city's governing administration, both in a practical and a symbolic sense. For a large part of the town hall's history, the deliberative and executive power in a city belonged to the same council. Emphasis has been on either the deliberative or the executive power at various times, but both remain associated with the town hall. The town hall is thus also a symbol of the city exercising administrative power. In the USA for example, 'City Hall' is used as a metonym for the city's government in everyday speech.

Third: the town hall is also a symbol of the city in relation to other cities, and also the city's independence from a higher central authority and the church. The town hall thus reflects the city's perception of itself – or at least the image that those in power have of the city and its significance. This role has grown more and more complex over time. One reason for this is that the city's administrative borders shifted, and the town hall has come to represent more than the city itself. Another is increased mobility: cities' inhabitants now comprise a far more heterogeneous group of individuals with a wealth of diverse cultural roots. One might say that he town hall's symbolic role has become less stable over time, particularly over the past century.

Nearly all town halls share these common denominators in some way, albeit with variations in how they are prioritised and rendered. With them in mind, we can begin to trace the history of the city hall until today.

Town halls from medieval- to early modern cities

When and where does the history of the town hall begin? Though inspired by Roman administrative buildings, the history of the building type can be said to have truly begun in the Europe of the Middle Ages. Increased trade brought more wealth and influence to European cities in the 1100- and 1200s. Prosperity and power meant that cities could demand a certain degree of independence from kings and sovereigns. This self-determination was secured in trade privileges, and it expanded as cities formed trade alliances such as the Hanseatic League, or defence alliances like the Lombard League. By entering alliances with one another, the cities could counter the monarchy's power over time.

Independence brought the need for governance; governance was a practical necessity for discussing a city's affairs, as well as protecting and manifesting the city's autonomy. Town halls were a practical and emblematic answer to the question of how to govern the city. While the town halls from the first half of the 13th century that remain standing today are not particularly spectacular, they contain elements that have been reinterpreted many times throughout history.

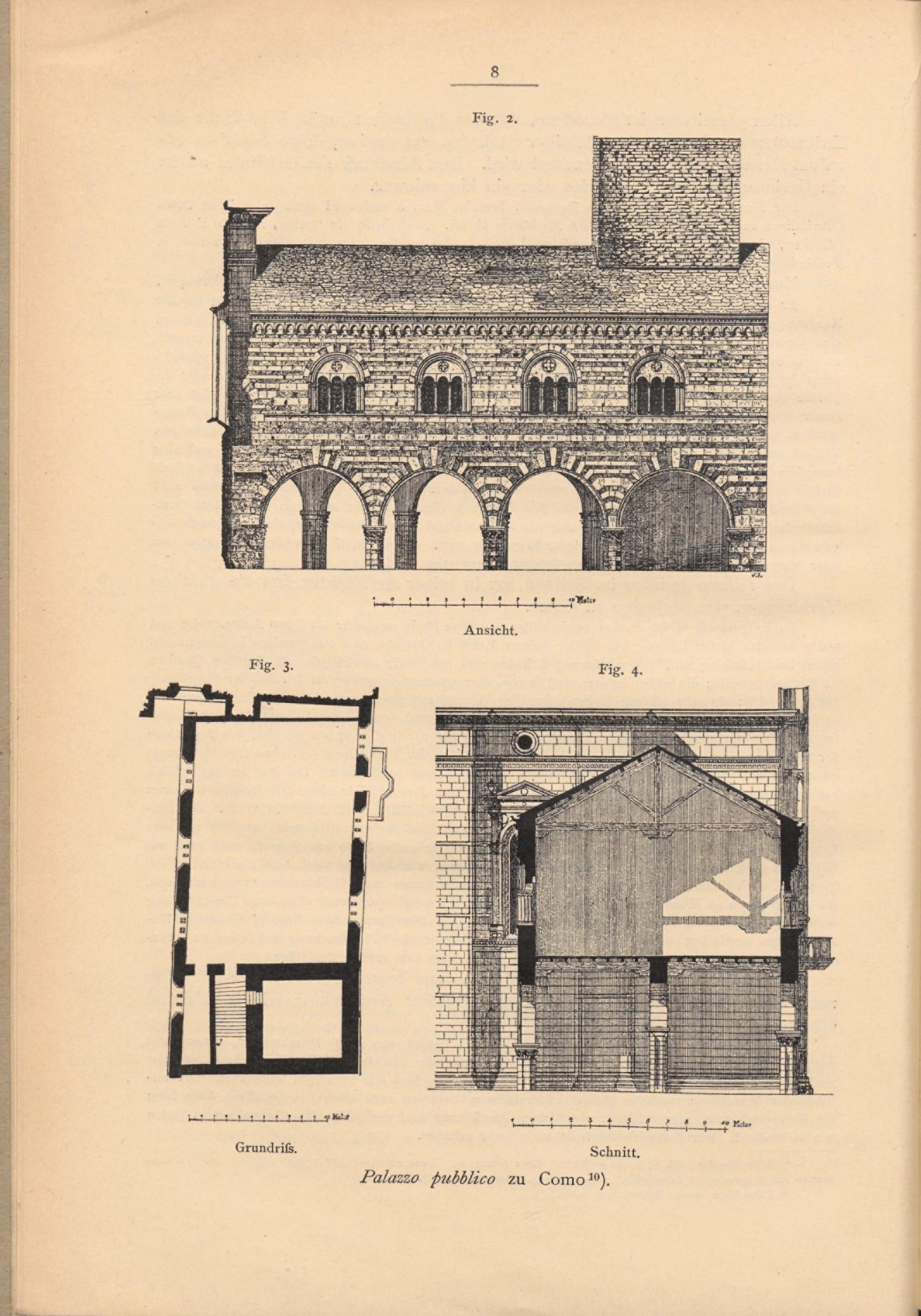

Palazzo del Broletto, Como. Handbuch der Architektur.

Como's town hall, Palazzo del Broletto, in what is now northern Italy, dates back to around 1215. The ground floor is an open space encircled by an arcade. With a roof overhead, the space was primarily used as a marketplace, but it could also be used for public debates. Above the open lower level is a hall in which Como's council convened to discuss issues of city governance and administration of justice. For a long time, city councils had a dual function, acting both as administrations and courts of law. Town halls (stadshus) and council halls (rådhus) are often situated in the local courthouse, even today. In Como, the hall on the upper level was originally connected with the open space below via a balcony from which one could address a larger group of people than what could be accommodated in the hall itself. Various elements from early town halls like this one are recurring: the public space, the meeting hall for the city's decision-makers, and the balcony as a platform from which one could speak to a group of people.

Some cities grew incredibly powerful in the 1200s. These were primarily cities in what is now northern Germany and northern Italy. The cities grew, and with them the need for larger town halls. Toward the end of the century, Siena and Florence erected two of history's most renowned town halls. The town halls in Siena and Florence were different from Como's, however; They resembled fortresses more than their predecessor. The space corresponding to the ground floor below the town hall in Como became interior courtyards behind walls. Another important difference was how central these town halls were in the cities themselves: both were erected in highly prominent places on the most important squares of their respective cities. In addition, these town halls were furnished with clock towers tall enough to compete with the noble families' watchtowers, as well as with the church steeples. They were an indication of a new power structure. The town halls' towers, interior courtyards and positioning on the city's central square are also recurring motifs in later town halls.

Piazza del Campo in Siena with Palazzo Pubblico. Andrzej Otrębski.

When the Black Plague and the catastrophic famines that tormented European cities throughout the 1300s had abated, cities slowly began to restore their populations, even to grow. Larger cities required more administration. Town halls' functions quickly grew in number. The city treasure needed a treasury; the city defence needed an armoury, criminals needed to be locked away somewhere – and more. All of these functions were soon consolidated in the town hall. In addition, as accounts-keeping developed, there emerged an urgent need for a workplace for the cities' accountants. One well known example is gli Uffizi in Florence, literally 'the offices', which were constructed in the late 16th century.

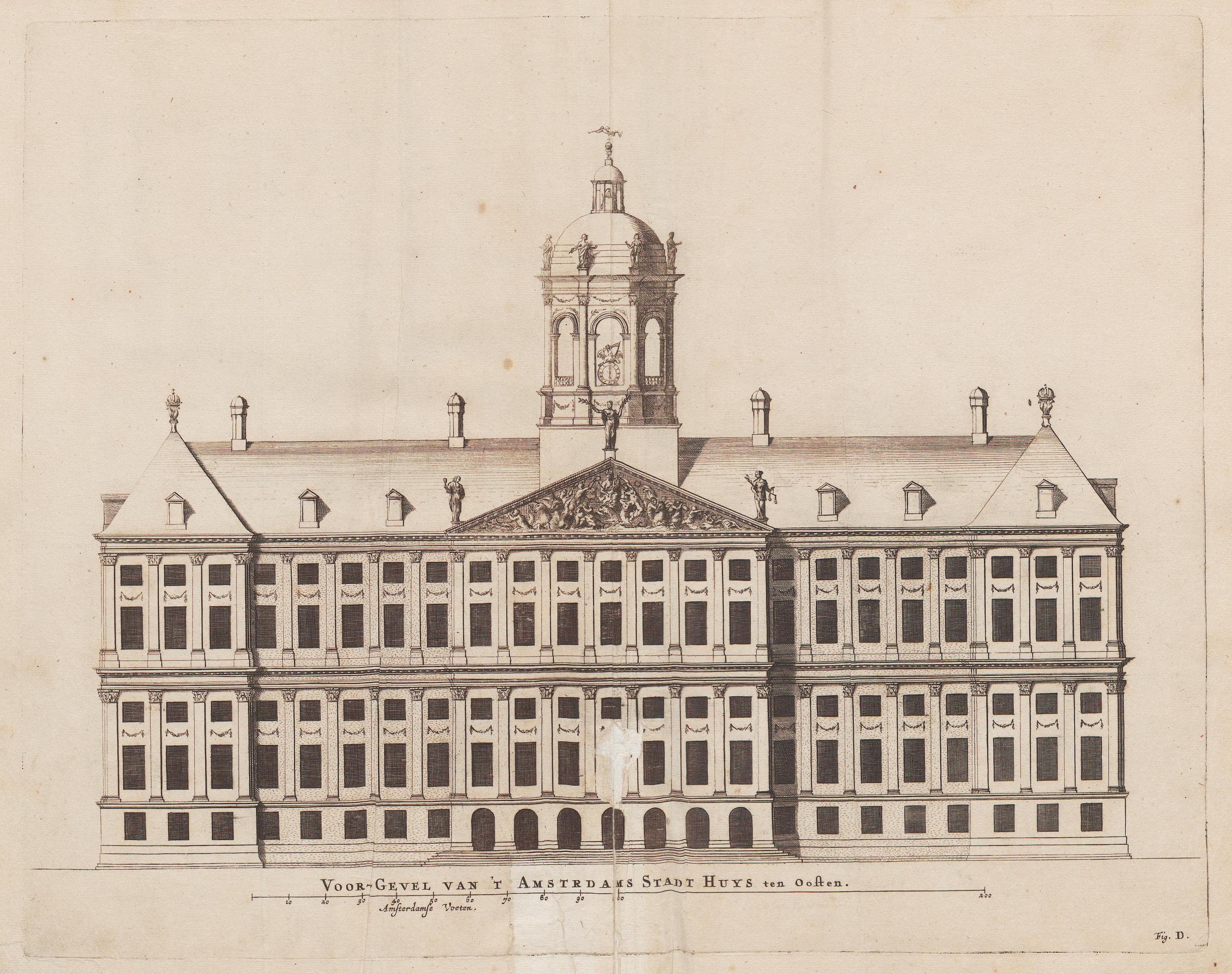

Stadt Huys van Amsterdam. (Heidelberg University Library. Public domain)

Trade patterns also changed in the 16th and 17th centuries. The newly independent federations in what is now Netherlands and Belgium became centres of economic development in northern Europe. The wealth generated by the East India Company flowed into Amsterdam, and the city commissioned the construction of what was perhaps the most elaborate town hall of the 17th century: Jacob van Campen's Stadt huys van Amsterdam (1655). It housed an impressive array of functions besides the council hall: the city bank, which granted loans; the bailiff; the insurance office; the armoury; a prison; a residence for the jailor and his family; a torture chamber, and much more. The era can be called the golden age of the trade cities. Over time however, power slowly shifted to the colonial powers' capital cities, primarily London and Paris.

Scandinavian town halls

Scandinavia was sparsely populated during this period, and its cities were not among Europe's most powerful. Numerous town halls and council buildings were built in Scandinavia in the Middle Ages, but it was not until the mid-1800s that building town halls gained momentum. Simplified, three shifts occurred in the 1800s that can be said to have laid the foundation for town halls being constructed just then.

The first was a significant increase in trade and a dawning industrialism, which primarily benefitted a new group of citizenry outside of the groups traditionally conducting business in cities. Industrialisation, faster transportation and rationalising agricultural reforms also led to rapidly growing populations in cities in the 1800s. Cities quickly went from being relatively small to becoming enormous units with overcrowding and large demands. The other shift was the introduction of liberty to pursue a trade around 1840. Prior to this, the guild system had limited political power to a very small, privileged circle of the haute bourgeoisie. In the absence of these limitations, political power become accessible to members of the citizenry who had found wealth through trade and industry, and they were more than eager to reform the city's foremost symbol to reflect their own visions. The third shift comprised the various municipal reforms that were introduced in Scandinavian countries mid-century, which granted municipalities increased independence from the government.

Together, these shifts led to more independent cities with fuller coffers and an administration to manage the needs and interests of more inhabitants. With the demise of the guild system, cities found it necessary to organise various functions formerly delegated to individual guilds – ploughing snow, street maintenance and firefighting are just three examples.

New tasks for the administrations emerged in the latter half of the 19th century related to gas systems, water supply and planning for expansion of cities beyond the city walls. As municipal responsibilities increased in number and scope, new and significantly larger town halls became necessary to carry them out. In addition to practical duties, newly wealthy merchants and industrialists wanted a dignified stage for social gatherings. Cities had long since been expected to provide accommodation and food for travellers. This took on new meaning as lavish and costly hotels were integrated into town halls. Many of the new town halls built in the second half of the 19th century boasted elaborate adjoining banquet halls and hotels – the city halls in Örebro and Sundvall are two such examples.

Örebro City Hall 1895. Photo: Alfred Michaelson (Tekniska muséet).

Central authorities' power over the municipalities continued to decrease as the century drew to a close. Courts of law and public functions began to be moved out of town halls. In Stockholm for example, an architecture competition was held in 1903 for a new town hall that would house both town hall- and tribunal functions; following a public debate however, the decision was ultimately made to separate the functions and construct separate buildings. When Ragnar Östberg's City Hall was inaugurated in 1923, it was thus a more specialised and unmistakably municipal city hall (kommunalt stadshus); in addition, its position seemed almost a counterweight to the palace and the parliament building on the opposite side of Riddarfjärden.

Stockholm City Hall 1925. Gustav Heurlin (Västergötlands museum).

Stockholm City Hall's tower made a conscious association to Venice. The tower itself is an architectural component frequently linked to town halls as a building type; at the turn of the century, the tower was perhaps the defining element that rendered City Hall easily identifiable. This is true for Martin Nyrop's Copenhagen City Hall (1888–1905), whose soaring tower was inspired by Siena's Palazzo Pubblico. Interestingly, the tower continues to be an important element for town halls, also since Functionalism began to shape architecture according to new and non-monumental principles. Arne Jacobsen and Erik Mørk's design for the town hall in Aarhus (1937–41) was originally without a tower. Many residents found the tower's absence to be an affront, which ultimately led to debate and the hasty addition of a tower when construction for the building had already begun. A number of Scandinavian town halls from the 20th century feature prominent towers, for example in Oslo and Västerås, and not least Kiruna's old town hall. It wouldn't be too far of a reach to say that the tower also served as inspiration for the town halls of the 1950s and -60s that were designed to resemble high-rises, such as those in for example Luleå, Boden, Sundbyberg, Solna and Bollnäs.

Copenhagen City Hall. Photo: News Øresund Jenny Andersson.

Aarhus City Hall (Det Konglige Bibliotek).

Changes to town hall design came rapidly in the late 1800s. Political representation was a central issue. Municipal reforms in the mid-1800s had given exclusive and unfair preferential treatment to the wealthy and companies that were given a right to vote depending on the tax revenue they contributed to the local municipal treasury or state coffers. Industrialisation created industry magnates, as well as a new group that sought to gain political influence: industry workers. With the labour movement came demands for a new political order. Instead of a system in which property controlled power, there were advocates for a system based on the individual and the individual's right to participate in politics. As the calls grew more persistent, the demands on town hall buildings changed. No longer would they be playgrounds for the city's elite – or give that impression – instead, they would open up for the broader masses. Town halls from the turn of the century and beyond were thus designed to include publicly accessible atriums; these could have a roof, like in Copenhagen, or be open, like in Stockholm. An invitation was thus extended for the general public to enter the city hall – at least a little bit.

Demands for broader voting rights led to more comprehensive changes. With voting reforms in Denmark (1915) and Sweden (1919), democracy and democratic leadership became central values to be transmitted by town halls. The question: 'How can democracy be rendered tangible in town halls?' was central for town hall design all the way to the 1960s. Democracy's very heart, the assembly chamber, grew to become an obsession of sorts, and it was the most prominently positioned room in the new town halls, with no expenses spared.

Falkenberg City Hall, with assembly chamber at the top (Swedish National Heritage Board/Riksantikvarieämbetet).

In order to emphasise its importance, the assembly hall was also rendered visible from many different angles in the façade – a reminder of the democratic processes taking place within. The town halls in Aarhus, Falkenberg (1960), Halmstad (1938), Bollnäs (1966) and Kiruna (1958–62) present the assembly chamber prominently on the building exterior. The very high-ceilinged assembly chamber in Alvar Aalto's Säynätsalo City Hall became symbolically both assembly hall and tower with a nod to Siena. Some took emphasis of the assembly chamber further still, extracting it altogether from the town hall and placing it in a structure of its own. While Arne Jacobsen's town hall for Rødovre (1952–1956) is perhaps the most explicit example, similar tendencies are discernible in the town halls of Luleå (1953–58) and Boden (1956–58), and internationally in for example Toronto City Hall (1959–65), where the administration and assembly chamber are decidedly distinct from one another.

The aspiration to render tangible democratic openness shifted around 1970, when the political winds turned once again. A municipal reform in that period led to the consolidation of municipalities, and ultimately to the dissolution of the differences between cities, market towns and rural municipalities. The municipalities that remained were thus far larger than before, and frequently included multiple urban centres. As a result, town halls, or council halls (kommunhus), came to represent larger territories. Another effect of the consolidations combined with the post-war expansion of the welfare state was that municipalities developed into gigantic organisations that employed increasing numbers of people and required more and more space. The future projected at the time seemed to promise still more municipal expansion; municipalities thus often placed municipal halls in locations that could accommodate future expansion. Newly constructed municipal buildings were often erected on the city's outskirts rather than on the central square, such as for example in Vellinge. In cases where municipal buildings were constructed centrally – such as in Nyköping (1962–1969) – the buildings themselves were overwhelming, dominating their surroundings. Nonetheless, in terms of space, it became apparent that some town halls, including the one in Nyköping, were far too small.

The 1970s were also marked by dissatisfaction with the government and a belief that it was effectively repressing certain parts of the political spectrum. In this climate, town halls were no longer designed as monuments to power, but rather as more discrete administrative complexes; new town halls were reminiscent of company headquarters. Presumably, the aim was to show that inhabitants' tax contributions were being used effectively, and that no unnecessary indulgences were being made. The town hall's role as an administrative structure was emphasised: the assembly chamber moved slowly further into the building, or it was relocated to the assembly hall of a nearby school. Architect Sten Samuelson designed a series of town halls in the 1970s and 80s, including town halls in Landskrona (1976), Ängelholm (1971–75), Lidingö (1970–75) and Malmö (1983–85). The former two preserve the character of monumental buildings positioned prominently in their respective cities, whilst the two latter are more anonymous buildings requiring signage to communicate to visitors that they are standing before a town hall.

Relatively few town- and council halls were constructed in the 1980s and 90s. During that time however, postmodern architecture prompted a renaissance of sorts for the idea of the city, with urban planners, architects and others rediscovering the qualities of the traditional European city. Town halls of the 1990s, for example in Skövde, returned to more monumental positioning in the city, as well as more elaborate, costly design. This was perhaps also due in part to municipalities themselves becoming more service-oriented in relation to residents; town halls should thus lend themselves to interactions with the municipality's various administrative units.

Town halls today

A small number of town halls have been constructed in Sweden since the turn of the millennium – for example in Södertälje, Lund, Täby, Kiruna and Växjö. Their design indicates certain tendencies, as well as contrasting developments. Rather than trying to pinpoint exactly what characterises the present, perhaps it is more useful to look at a few of the central questions in contemporary town hall design. Returning to the roles presented in the introduction to this text, certain questions become discernible, the answers to which may seem different when seen through a contemporary lens.

Kristallen in Lund. Photo: Adam Mörk.

The first of these roles concerned the town hall as the primary space – and stage – for the city's political life. How should that political life be understood today? In recent years, town- and council halls have frequently been built in central locations – not on the city's main square, however, but adjacent to its railway station. In some cases, the town hall is positioned directly adjacent to the train station, such as in Södertälje. Sometimes the town hall and the railway station are integrated peripherally, as in Lund, and sometimes the integration is comprehensive and complete, as in Växjö. This development aligns with a broader urban planning trend in which cities are densifying around their railways. The placement may also indicate that town halls are perceived as service-oriented buildings that prioritise accessibility for citizens rather than their role as a political stage; from the citizen's perspective, this clearly makes sense. There is, however, very limited space for general political congregations in front of the town hall, for example to gather in protest against decisions. The question is whether there is any room for the town hall to function as a political stage anymore? The municipal council remains the decision-making body in which decisions concerning the public are made. Most of the council halls built in recent years have not prioritised assembly chambers; often, these have been located in other buildings altogether. In an era in which threats to democracy seem to be coming from multiple directions however, we may also ask ourselves whether it is time to return to the old role, where the town hall's visible assembly chamber is an open, public political stage, in order to support and strengthen the democratic process?

Kristallen in Kiruna, exterior and clock tower. Photo: Henning Larsen Hufton + Crow.

The second role from the introduction to this text concerned the town hall as a seat for administration, both practically and symbolically. Today's municipalities are responsible for the administration of enormous and multifaceted operations, and the town- or council hall is the administrative centre of these operations; administration should thus be service- and user-oriented – not politics. Openness and accessibility have been keywords in the construction of town halls in recent years – central values that the building should communicate according to practically every architecture competition for town- and council halls. The physical manifestation of openness and accessibility varies from one municipal district to another. A number of practical considerations need to be made, including requirements regarding employee environment and safety. In practice, many town halls are designed with gradated accessibility: outermost is a completely open reception area; beyond this is a meeting area in which employees and the general public can meet, and the innermost area is primarily reserved for those who work there. These three sections are often linked visually by an atrium that transects the entire building and reinforces a sense of openness. Another possible result of these values is that many of the town halls from recent years have been constructed as office buildings with glass façades. Whether the glass façades are an expression of a literal transparency for citizens or simply a logical effect of surface requirements, construction depth and daylight provision regulations, remains undetermined.

The third role is probably the most difficult to contend with for architects today. If the town hall should be a representation of the city itself, how should its design capture the many nuances of a multicultural society? Whose voices and which identities should be granted precedence in the design? The welfare state of the 20th century sought to capture and express a far more homogenous population, and today's welfare state is far more heterogenous. This heterogeneity is accompanied by different perceptions of what town halls represent. European town halls have traditionally represented liberty and self-determination, whilst comparable town halls with nearly identical exteriors erected in colonies by colonial rulers have represented the opposite. In cities such as Mumbai, Kolkata, Jakarta, Sydney and others, town halls have been a symbol of the repressor. The question, then, is this: How can architectural design communicate openness and accessibility in a broader cultural context in which one symbol can simultaneously express diametric opposites?

Town halls must thus be more than the simple continuation of the monumental town hall competing for attention with the church. It must offer more, or else risk being perceived as the expression of a dominating and excluding power structure. The result is a difficult balance act for every municipality planning a new town- or council hall. Perhaps the question should be formulated thus: If accessibility and openness are the core values in demand, shouldn't these values be understood as something that necessarily must be integrated when shaping the design process of the town hall itself, with a range of ways for citizens to participate and where different groups have a chance to be heard throughout?

The three roles discussed in this section are central issues to which the design of town halls is expected to respond. These responses take on different character depending on context, power structures, the society’s composition, political winds, economy, legislation, and more. And these shifts in how issues present themselves are precisely what generates opportunities to develop the town hall's role and functions in the city. How the problems formulated above will affect the town halls of the near future remains to be seen, but the town hall will probably go on relating to the history of the building type, both through variation and continuity.

SOURCES:

Swedish town halls:

Karin Arvastson & Cecilia Hammarlund-Larsson, Offentlighetens materia: Kulturanalytiska perspektiv på kommunhus (Carlsson: Stockholm, 2003).

Eva Eriksson, ‘Från rådstuga till förvaltningskomplex’ i Arkitektur 6 (1978), s. 2–8. Håkan Hökerberg, Kommunalhus som uttryck för samhälleliga ideal och värderingar.

(Göteborgs universitet: Göteborg, 1994).G

egor Paulsson, Svensk stad, del I & II (Bonniers: Stockholm, 1954).

Scandinavian town halls:

Gerd Bloxham Zettersten, Nordiskt perspektiv på arkitektur: Kritisk regionalism i nordiska stadshus 1900–1955 (Arkitektur förlag: Stockholm, 2000).

European city halls

John Stewart, Twentieth Century Town Halls: Architecture of Democracy (Routledge: Abingdon, 2019).

Town halls seen globally

Swati Chattopadhyay & Jeremy White (red.), City Halls and Civic Materialism: Towards a Global History of Urban Public Space (Routledge: Abingdon, 2014).